by Denise Wilson, April 11, 2022

Few words are much easier to feel than to describe, but belonging is one of them. In any social or work setting, I can tell you in an instant whether I feel I belong or not and to what degree, but if you ask me to neatly and concisely define what belonging is and why I feel it when I do and don't feel it when I don't, I will stare at you blankly - as if you just landed in front of me from another planet.

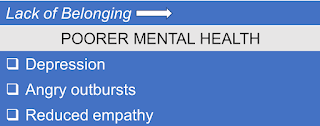

Wikipedia reports that belongingness is a strong feeling of being accepted within a group, of being part of something bigger than ourselves. Psychologists Baumeister & Leary argue that the desire for belongingness is so strong that it is a basic human motivation, a need that everyone, regardless of culture, status, race, ethnicity, gender, or anything else, must satisfy to avoid dire psychological consequences. Such dire consequences include stress, anxiety, grief, pain, loneliness, and other forms of negative emotional states that, when chronic, lead to depression, suicidal ideation, and other debilitating psychological states. Belonging needs can be met at work, with family, at church, with friends, or in any other community where a person can be an accepted member of a group.

At work, meeting the need to belong extends beyond having a place of impact and value in an organization. While these things are important and provide a sense of fit and purpose in one's work that contributes to job satisfaction, a true sense of belonging will emerge only when positive relationships at work are valued alongside contributions to the organization. An employee feels like they belong at work when they feel they can be their whole and authentic self in the workplace and when they are accepted for such.

But sense of belonging is not only important to the employee; it is also crucial to the organization. Employees who feel a strong sense of belonging are more engaged in their work, contribute more, share more ideas, make better decisions, and collaborate more readily. All of these things are critical to supporting the innovation, excellence in design, and problem-solving capability that are the hallmarks of good engineering.

Belonging is a fundamental psychological need but is often neglected in the workplace. Perhaps this is in part because the connection between belonging and productivity is not widely recognized or understood. Perhaps this is also because belonging can be a difficult feeling to dissect. For many of us, it is easy to gauge our sense of belonging, but it is often difficult to put our finger on exactly why we feel like we do or don't belong.

So, the next time at work when you notice you are experiencing a feeling of belonging, take a moment to try to understand why. Ask yourself a few questions to raise your self-awareness:

- Do you feel accepted at work?

- Do you feel meaningful connections to one or more coworkers?

- Do you feel welcome in your work group?

- Do you feel that your coworkers support you in contributing to the group?

- Do you feel comfortable at work?

- Do you feel like you can be yourself?

Engineers tend to be data-driven people. Things that can't be quantified sometimes make us anxious. But belonging is actually not some sort of fuzzy, squishy feeling that floats in the ether of everyday life. Rather, it is grounded in good relationships. It manifests as positive interactions with others, and in the stability of those relationships and bonds that result from the positive interactions. And it can, in fact, be measured!

And it should be measured, because belonging matters to organizations just as much as it does to individuals:

"A sense of belonging is what unlocks the power and value of diversity." (Cornell University)

Please help us to better understand belonging in the engineering workplace by taking our survey (open to engineers and computer scientists as well as those who have worked closely with them):

More about Belonging:

Cornell University Diversity and Inclusion (2022). Sense of Belonging.

Huang, Steven (2020). Why does Belonging Matter at Work? Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM).

University of Washington. Understanding and Evaluating Belonging in Higher Education.

References:

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation, Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497-529.

Gabriel, S. (2021). Reflections on the 25th anniversary of Baumeister & Leary’s seminal paper on the need to belong. Self and Identity, 20(1), 1-5.

Denise Wilson is a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington. Her research interests in engineering education focus on belonging, engagement, and instructional support in the undergraduate engineering classroom.